Memolines ~ Toys scattered everywhere, but I didn't choose to say "Clean up now" — Using questions to help my child learn to think independently

This takes constant practice.

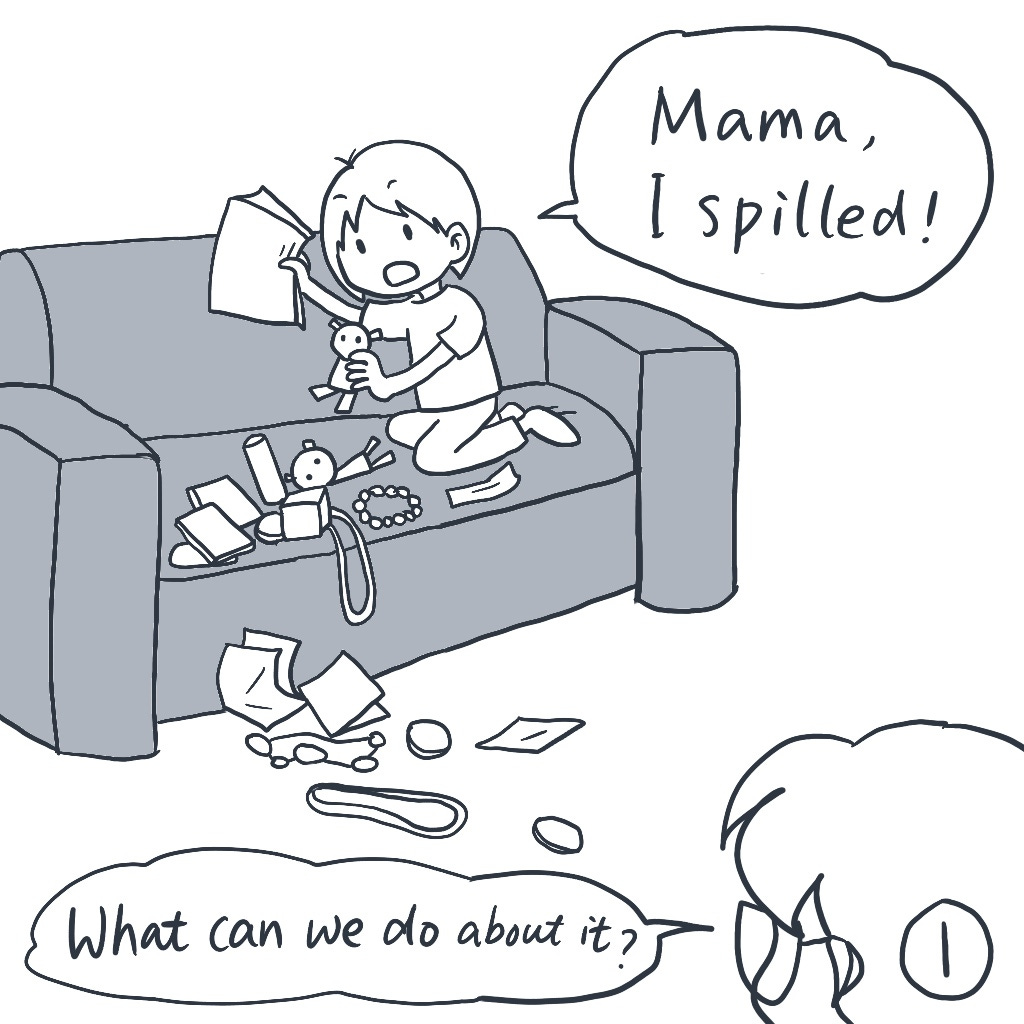

The other day, my toddler was playing when toys from her little bag spilled all over the couch. I heard her call out, “Mama, I spilled!”

I asked, “What can we do about it?”

She answered, “Clean up,” and started putting the toys back one by one.

In that moment, I had several options: tell her “clean up now,” help her do it, or get upset. But I chose to ask her a question and let her figure it out herself.

Similar situations happen often. When milk spills on the floor or something drops, she calls for us. I often resist the urge to tell her what to do directly and instead ask, “Oh no, what should we do?” She usually responds with “wipe it” or “pick it up.”

I’m not saying directly giving answers is wrong, but I’ve found that guiding through questions helps her think things through and reach her own conclusions. Over time, she’s forming habits: pick up what drops, wipe up spills, clean up scattered toys. These actions come from her, not from my commands. As she grows older, especially when facing challenges, she’ll think about what she can do rather than waiting for someone to tell her the answer.

The book Humble Inquiry talks about how those in positions of authority need to be careful about directly commanding those without authority. I think this especially applies to parent-child relationships.

When children are young, we can use force to make them comply. But if parents constantly say “you should do this or that”, children become dependent, feeling they don’t need to think for themselves. Plus, this “should” type of expression easily triggers defensiveness—the first reaction is often to resist the command rather than accept it.

I’ve noticed that if I say “you should put the toys away,” my toddler might say “no” or drag her feet. But if I say “wow, so many toys on the floor, it’s so messy. What can we do?” she’s much more willing to clean up.

When guiding through questions, the key is staying curious about how my child will respond rather than having a preset answer in my head. For example, when we discover it’s raining outside and I ask, “It’s raining. What can we do?” she might say “wear a hat,” “splash in puddles,” or even “stay home.” If I just tell her “put on rain boots and get an umbrella,” not only does she lose the chance to think, but I also miss the opportunity to understand what’s on her mind.

More importantly, when we ask “what do you think we can do,” we’re not just treating her as an independent person capable of thinking—we’re building trust between us. When a child feels her parents respect and believe in her rather than commanding and controlling her, she’s more willing to cooperate and more willing to seek help when facing difficulties instead of hiding problems. Even though my toddler is still very young, this respect leaves an impression, letting her know she’s capable of solving problems.

Honestly, this approach takes constant practice. When we are in a rush, saying “hurry up and put on your shoes” is definitely faster. When she’s not doing something well, it’s hard not to just give her the answer. But we do our best to immerse her in this environment of independent thinking. For example, when she doesn’t like eating vegetables and gets a bit constipated, we ask, “How can we make poop softer?” At first, she might just repeat what we’ve said—“drink water, eat vegetables, soft poop”. Gradually, she would start thinking and understanding why these ideas and which of them work best for her, and act accordingly. This is a long-term process that requires patience, giving her time to think and try. That matters far more for her growth than saving a few minutes.

You may be interested in the following: